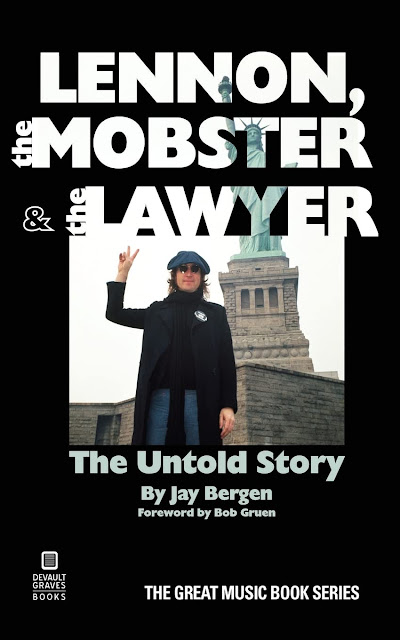

John Lennon's Lawyer: A Conversation with Jay Bergen, Author of "Lennon, the Mobster & the Lawyer: The Untold Story"

Jay Bergen's recent book "Lennon, the Mobster & the Lawyer: The Untold Story" is a snapshot of the former Beatle during an eventful, but little documented, time in his life.

John had just reunited with Yoko Ono and was back in New York after his "Lost Weekend" period spent with May Pang in Los Angeles. Looking forward to stepping away from the music business in order to focus on domestic life, Lennon instead found himself embroiled in a lawsuit to stop the unauthorized release of songs he'd recorded for his Rock and Roll LP.

To help settle a plagiarism suit filed over the Beatles' "Come Together," which lifted some lines from Chuck Berry's "You Can't Catch Me," John had agreed to record three songs owned by Big Seven Music, the publisher of Berry's tune.

Big Seven was owned by Morris Levy, a mob-associated businessman notorious for filing shakedown lawsuits and screwing over his artists. He was famous for once having beaten up a policeman so badly that the cop lost his eye, and he was the model for "The Sopranos" character, Hesh Rapkin.

When Lennon loaned him a tape of rough mixes from the Rock and Roll sessions, Levy hatched another scheme. Claiming that John had given him permission, Levy pressed up an LP of the mixes titled Roots: John Lennon Sings the Great Rock and Roll Hits and started marketing it with cheesy ads on TV.

For John, this was too much, and he sued to stop Levy from selling the record. Bergen was the attorney retained to represent Lennon in court, and his book covers his time spent with ex-Beatle.

"Lennon, the Mobster & the Lawyer" details the court case and features many transcripts from John's testimony, which offers fascinating insights into his working methods in the studio, and how involved he was in preparing the official Rock and Roll LP for release.

It was a pleasure to talk to Bergen about his time spent in John's company and his experiences representing him in court.

Here are excerpts of our conversation. Thank you, Lisa, for the transcription!

John Firehammer: I really enjoyed reading your book. I’ve read tons of Beatles and John Lennon books but this one presented a really interesting perspective and highlighted an interesting time in his life, too, just before he departed his public life for a bit and did his househusband period. It really adds a lot to what we know about him.

Jay Bergen: Thank you for saying that and noticing that, because that’s why I wrote the book.

What do you hope people take away from it? What do you hope they learn about John and this episode in his career?

Well, I think, after all of the bad publicity, after his lost weekend in Los Angeles starting in 1973, and then running through and into part of 1974, when I met him on February third ‘75, I believe that was the night that he went back to Yoko in the Dakota the first time.

And that was the beginning of this period when he dropped out, and he got very involved in the case, and I really wanted people to know about this period of time when he was not, kind of the rock icon. He wasn’t playing that role or acting that role, but also how he really got involved in the defense of the case, and also his perfectionism and the testimony that he gave in the trial, about how he and the Beatles, as he said, learned the trade.

He really was a perfectionist, and when he was making his own records and producing his own records, how he kind of taught the band the songs and the arrangements and all that. That’s what I really wanted people to come away with, and I think you understood that and you got it, and that’s what caused me to write the book.

You know, I’ve been carrying around these five or six bankers boxes of files for 40 years, through like five moves, and they were always with me, but I never really looked at them, until five years ago. And that’s what got me going

I was struck by your discussion about his learning the trade and his level of professionalism and so on. I knew he would be very involved in the music and cared passionately about the music and all the aspects of it. But he also was very involved in the packaging of the album, and all of the small details that go along with that.

That was new information to me, that he cared that much. I mean, it makes sense that he would, but I also sometimes got the impression that he could be very casual and cavalier and not care about some details. But he was very much involved in all of those, it sounds like.

And then also, there’s an impression that’s conveyed a lot about him that he wasn’t a very technical person, that he didn’t understand technology very well.

There’s a story about “Strawberry Fields,” where there’s two versions of the song and they merged them, even though they were recorded in different keys, and he just sort of left it in George Martin’s hands to try and figure out how to do that.

So the impression you get is he didn’t really understand how recording worked, or the difficulty of adjusting speeds and all of the details. But my impression from reading this is that he knew actually quite a bit about how sound is recorded and how records are manufactured. Does that sound right to you? Is that your impression too?

Yeah, yeah, because he was very involved in the technical aspects of it, and he knew what he could do and what he couldn’t do ….

I don’t know whether it came across clearly in his testimony, but he was not really satisfied with the record, a record, until right at the end. When they were making the master, before they made the metal parts in the cutting room. He would want the opportunity to change something right at the last minute, which he did when he cut out “Be My Baby” and “Angel Baby,” which as you saw in the book, that record … when I talk about the song, I’m talking about Rosie and the Originals doing “Angel Baby,” that was one of his classic songs, and he had to take it out because it was kind of a mess, and it was too long.

The other thing I’m sure you noticed, that he was very focused on [is] that he wanted the record to be loud, and once you got beyond 20 minutes, it started losing the sound, losing the level.

Those are great details, especially to folks who are interested in the process of recording and his level of involvement, and all that. I think that’s one thing that really came out in this.

One thing I was interested in getting your perspective on is that deposing somebody is a lot different than interviewing somebody. They’re sworn to tell the truth, for one thing.

I think maybe you get different information in a deposition than you would in just a casual magazine interview, for example. What you present here is different than what you might see in a book of interviews with John Lennon.

That’s a very good point. One of the things I learned very early in my career is that the facts in a case were critical..I always told clients you gotta tell me everything, the good and the bad, because I don’t want any surprises.

So I spent a lot of time with John, and May Pang, and some of the other important people, really getting the facts down so that we could tell the story. And the story was really important. And the great thing was that our story never changed. It was pretty straightforward.

And John was a very good witness. I think it may have had something to do with the fact that he had done so many interviews over the years, and he was very smart, as I’m sure you know and realize, and he was very focused on this because he decided very early after we started spending time together, that he was not going to settle this case. He wanted to get rid of Morris Levy, who he thought had really grifted him into this case with a pretty weak copyright infringement case.

I think you convey that perfectionism really well: His dismay, his concern that this substandard, basically bootleg record was out. He was more concerned about the music on it than losing the proceeds, or it cutting into his sales. He didn’t want that out in the world because it sounded the way it did, and it didn’t capture him at his best.

You’re a hundred percent correct on that, and you picked up on that in the book.

If you remember, when we were in the counterclaims part, and we got to the part where we had the audio equipment from the Record Plant brought in, he did not want to sit there and listen to even one track of the Roots album. And I told him, “You can’t leave. You gotta sit there.” And it was painful, because he knew what it was going to sound like because he had spent so much time.

...I think it really gnawed at him, that this was out there, and people were going to listen to it.

And Levy was a very bad guy. I wasn’t aware about the assault case that you wrote about in your book. It was beyond him being just a grifter, con man type guy. He was actually physically violent as well.

Oh yes, oh he was. One of his partners, his secret partners, Thomas Eberle, a few years before this happened, was gunned down coming out of his mistresses’ house in Bensonhurst in Brooklyn. Morris was hooked up with some very bad people. And had been from an early age.

John spent time with Levy and seemed somewhat fascinated with him. Do you have a sense of what that was all about or why he spent time with him, what his interest was?

I think he described Morris as a character. And Morris was a character. He kind of talked with this throaty … voice because he claimed he had polyps. And he was a rather large man, he was like six one, I think, and a little on the beefy side, and he had this reputation. I’m not sure how much of the reputation John knew about, but we never talked about it. I just steered away from that.

As far as you know, he never became aware of the depth of [Levy's] involvement with organized crime?

No, I don’t think he was. I don’t think he was. And as I told in the book, with Klaus Voormann who told me when I interviewed him a couple months before the trial started, out in Los Angeles, that John was very naive about business...As [John] said at one point, "That’s not my job. Business is not my job." He was a very shy person, too.

What were some of your impressions of John when you met him? What struck you? Was it the shyness, his intellect or...

The intellect came across, and that first time we met, which was a surprise, when he came to this meeting [between Bergen's firm and lawyers from Capitol Records]. [The] thing that he talked about right away was, "this record is going to be a mess. This Roots album is really going to damage my reputation."

And there was some talk, preliminarily with the Capitol lawyers, about possibly getting an injunction and stopping Levy. And I said to him, look, that isn’t going to be easy. And secondly, one thing you don’t want to do in a situation like this is start the battle, start the fight. Because I kind of described litigation and trial work like that, it’s a war. Once you fire the first shot by filing a complaint, then you kind of lose control of what’s going to happen next. And I didn’t want to do that.

And... John made it very clear, the other thing was, he wanted to get the Rock and Roll album out...he really wanted to finish the album the way he wanted to finish it and get it out.

One thing I thought was cool is that you had a bond with him over early rock'n'roll because you were into it, and obviously he was steeped in it. And I also thought it was interesting that you showed him different sites in New York, Grand Central Station, the Chrysler Building and things like that. Some of those personal moments I thought were really fun to read about.

Once I got over the shock of John Lennon walking into this room, [chuckles] which I did not know he was going to be at this meeting. I’m not even sure that the Capitol lawyers … My partner David told me, “Can you go to this meeting with the Capitol lawyers?” And I said, “Yeah.” He didn’t say to me, you know, “John’s going to be there,” because I don’t think David knew either.

So once I got over that shock, and of course the thrill of representing him and being involved in this thing, I tried to treat him like I treated all of my clients. They’re my clients, we can be friendly, but we’re not going to be buddies, we’re not going to be hanging out. It’s going to be business, but it’s also going to be a very friendly and a collaborative relationship, because I think that’s very important in the work that we were doing.

So he kind of got into that. And I took him to Grand Central Station, not so much because it was Grand Central Station, but we were only a couple blocks away, and I’m thinking to myself, we gotta go someplace for lunch, and I thought of the Oyster Bar. Well, he’d never been in Grand Central Station.

So, as I describe, we went through this routine where he whispered to me, “Jay, can we sit up against the wall? You sit with your back to the wall, so I’m facing you, and not the crowd.” And then there was a great story with the woman who stopped in front of him and said, “You’re George Harrison?” [laughs]

So it gave you a window into life as a Beatle, I guess.

Well, the other thing is that if she would’ve asked him, I’d always wondered, if she would’ve asked him for an autograph, I bet he would’ve signed “George Harrison.”

Probably! [laughter] That would be worth quite a bit of money, a John Lennon forged autograph for George.

Yeah, all those little details are really fun. And like you said, it was a professional relationship but you were obviously required to spend quite a bit of time together and to be honest with one another and you learned a lot about him as a result. A really unique relationship, too, in a lot of ways.

I never saw - John never smoked, and he was a big smoker I’ve heard - he never smoked when we were together. Of course we never had a drink. He never used bad language, although he certainly, when we had lunch at Sloppy Louie’s [a seafood restaurant Bergen suggested that became a favorite of Lennon's], he was very upset by the fact that he and Yoko were spending all this time [in court]. And that was another interesting thing, that he didn't have to be in court every day. But they, he called me at midnight the night before the trial, “Can Yoko come?” and [I said] “Yeah, absolutely, I’m sorry I didn’t invite her,” and they came every day. Morris was not there every day. Morris was not into it.

What do you think was behind that? He was just so concerned about the case, or did he want to present a level of professionalism in court, or a little bit of both? What do you think drove him?

John? I think that he, and again, this wasn’t something I said to him, "You and Yoko have gotta come here every day." I think he just decided that this was so important to the two of them that they had to be there. They had to show, I don’t know, show the flag, so to speak. That is was important that they come in every day, and those were the early days of when you had to go through a metal detector. So we would come into the courthouse every morning and go through the metal detector. And to this day, I don’t know how [Lennon's photographer friend] Bob Gruen sneaked in the camera into the courtroom, but he did. And then, we’d leave at lunch, come back. I think it was just again part of his, not perfectionism so much, but I think his dedication to this case. And once the counterclaims were over, that last day, that [Rolling Stone writer] Dave Marsh finished his testimony, that was it.

He was done.

He was done. He had done his part. And all through the trial, Yoko was very, very quiet. She did not interfere and make any suggestions or anything. I think once she became convinced that I was the right person to represent him, she was just hands off.

What was your impression of her overall, just in terms of her personality and character? You said she was very quiet, so it might have been hard to get a sense of that.

Well, but she was, Yoko was very smart. When I went up to the Dakota that day, and I hope it was clear in the book that John was not in the room. It was just the two of us, and she had read both of those complaints, and she asked some very pointed and direct questions. She understood what was going on, and was very smart and expressed their concern.

John had told me the same thing, we’re very worried about this case, and we want to just hold down the amount of money that John is going to owe Morris. Anything like this, in any litigation like this, there isn't any such thing as a slam dunk. I wasn’t about to start guaranteeing that we were going to win, but the fact that John was so involved and helpful, we basically, which I’m sure in your career you’ve noticed, that you have to be prepared, when you do interviews or whatever, you have to be prepared. You can’t just walk in and start winging it. So we were prepared. And we really out-prepared Levy and his lawyer.

Yeah, it sounded like [Levy's] legal team didn’t do him any favors, from what you wrote.

I don’t know what he was thinking. And I think he deliberately blew up the first trial, before the jury in front of Judge McMahon, who I knew, I had met him, and I knew his reputation for being a stickler for having the lawyers being prepared, and moving his cases along.

That’s the other thing I wanted to ask you about, is [Judge Thomas P. Griesa's] passion for music. He became very interested in how John worked, and his music, and all of the aspects of that. That was a big plus, I imagine, and being very prepared and better off than Levy’s side. You had a judge who was pretty interested in what John was up to, it seemed like.

That was a stroke of good fortune. And then if you really look at that picture that Bob took of John looking at the judge, and he’s got his hand out, and he’s pointing, and the judge is looking directly at him. And then in the foreground, is [Levy's attorney William] Schurtman, with me off to the right standing at the lectern where I had my notes, and Schurtman realized that these colloquies, these conversations between the judge asking questions and John answering, they were not good. [laughter]

Yeah, to say the least.

And he kept jumping up and trying to interrupt this sequence, and the judge just didn’t pay any attention to him.

That’s fascinating, yeah.

That was fascinating, because, here’s a man who told us the afternoon that we went down to court, and he had just been appointed, "I don’t know anything about the Beatles or John Lennon," I mean, he knew who they were, he knew the names, but that was it. And when I told John the next day, John and Yoko when they came in, I said, we’re now gonna give this judge, when you testify, a tutorial on rock'n'roll, the Beatles, John Lennon’s music, and how you made records.

Another thing I was interested in is the process or putting your book together. You said you had these court files with you and lugged them around … and the transcripts are just great and really entertaining to read through and informative. I was wondering if, there were no tape recordings of these at the time?

No. What they have is, they have these court reporters who kind of rotate in and out of the room, because at the end of the day, in a trial like that, by 7, 7:30 in the evening, you get a transcript. There’s no tape recordings, not in those days. I think maybe today they might do that. But these are people who just transcribe the testimony, and then you have the actual transcript that you can look at before you go into the next day.

They’re such a great document. I’m really interested from the historical standpoint of, obviously the Beatles are going to be with us for a while longer in terms of people being interested in learning more about them and the history, and so just having those transcripts is really important as a historical document.

One of the things that happened was that, and this took place years later, but when Gruen was in court that day to take the photos, he became so fascinated with the testimony that he stayed there the whole day. And later on, he said to me, “You gotta put this testimony in the book.” And I said, “I’m going to. I’m not going to put in every bit of it, but I’m going to put in what I think is the most important and critical points that demonstrate John’s dedication as a professional.” But there were some people in the beginning of writing this book that said, “You can’t put too much of this testimony in.” And that was one of the reasons, that was another reason I wrote the book, because I wanted people to be able to read the testimony and have, you could almost hear John’s voice.

I found it really compelling, for all the reasons I talked about. It corrects some assumptions I think people make about John and gives you a unique window into his working process and how he viewed everything and how involved in everything he was. I think it’s really fascinating. … It sounds like you’re doing some appearances and lectures and so on at the Beatlesfests and things like that. What else is going on, as far as, what happens next with this project?

Well, I hired Bob Gruen’s publicist, and she’s been in the music business for years, and I just want to keep publicizing it and getting as many people as possible exposed to the book.

You speak really well, so I would imagine it would be a really great presentation at a Beatlesfest to hear about all of this from you. There’s this quote on the back from ["Let it Be" director] Michael Lindsay-Hogg about "HBO, where are you?" And it seems like it would be a good documentary project, too.

I originally talked to somebody, a documentary filmmaker about a documentary. But I think what really would be better, because a lot of people aren’t around any more, so a documentary would be really hard. But what I thought almost from the beginning, when I started getting into the writing and everything, would be a series of maybe eight episodes or 10 episodes, so you could tell the whole story.

I did do a 90-minute live show, that I had videotaped, I may be showing that at the Beatlesfest, but that only told a little part of the story. But that was kind of the germ of the rest of the book. I did it six times in 2018 and 2019.

I actually did it at the 92nd Street Y in New York City, which is a kind of a cultural center, and we sold out two nights, probably 200 people. In fact, I’ll tell you a funny story.

I hadn’t spoken to or seen May Pang in many, many years, and the first night we did the show, Bob Gruen came, somebody who was one of Yoko’s long-time assistants came, I don’t know whether Yoko asked her to go or told her to go, but she came, and this is somebody that Gruen knew, but when I walked up to start this multi-media show … who’s sitting in the front row, but May Pang!

That’s great.

And it turned out that a girlfriend of hers was looking on the website for the 92nd Street Y, and they have all kinds of shows and lectures and book discussions and everything, and she saw my name. She called May and said, “Who’s Jay Bergen?,” and May said, “Well, he was John’s lawyer and blah blah blah, why?” “Well, he’s talking. He’s giving a talk at the 92nd Street Y in a couple of weeks.” So who shows up but May and three of her girlfriends. [laughter]

That’s amazing. Jay, your book was really fun to read and it's been a pleasure talking to you!

---

Visit www.lennonthemobsterandthelawyer.com for more information on Jay Bergen and his book

Comments

Post a Comment